Anna Mikita was murdered by her second husband in the small Slovakian village of Lukov-Venecia some time after 1889 and before 1906. The life insurance policy taken out by her son, John (Joannes), in Cleveland during the 1920s told the tale: Father, “deceased in old country 1887” and Mother, Anna Mikita, “killed by husband” (length of “illness” inflicted at the hands of this second husband was noted as “3 days” but without a date of death). For a genealogy researcher, this was gold, but for the great great granddaughter of Anna Mikita, not so much. Poor Anna Mikita. I dove into the detailed church records of the village searching for answers.

“Diving in” implies a smooth and rapid entry into the clear waters of organized and detailed logs of the births, baptisms, marriages and deaths of my Slovak ancestors; what I did was more of a belly-flop into records written in Greek, German, Latin, Hungarian and Russian and into a Carpatho-Rusyn village of Greek Catholic tradition that involved a very small database of boy and girl names: Joseph, Michael, Joannes, Georgius, Petrus and Julianna, Anna, Maria, Paulina, Susanna. Dwellings by house number helped me sort families, and on a large white poster board I drew the village–placing my relatives immediate and distant in their respective houses. I went back to the year 1800 and moved forward, gathering a sense of community and belonging as I peered through that small window into the past- how nice, Julianna and Michael in House #6 had a baby boy! (Also named Michael, which would be less confusing had it not also been the name of the infant boy they lost to febris nervosa- which didn’t sound good- 15 months earlier.) Hours, days, and weeks passed. I taught myself enough Latin to read through the sacred, scripted books online that trailed off my screen and drifted the now-living dead into their crudely drawn squares on my treasured poster board village.

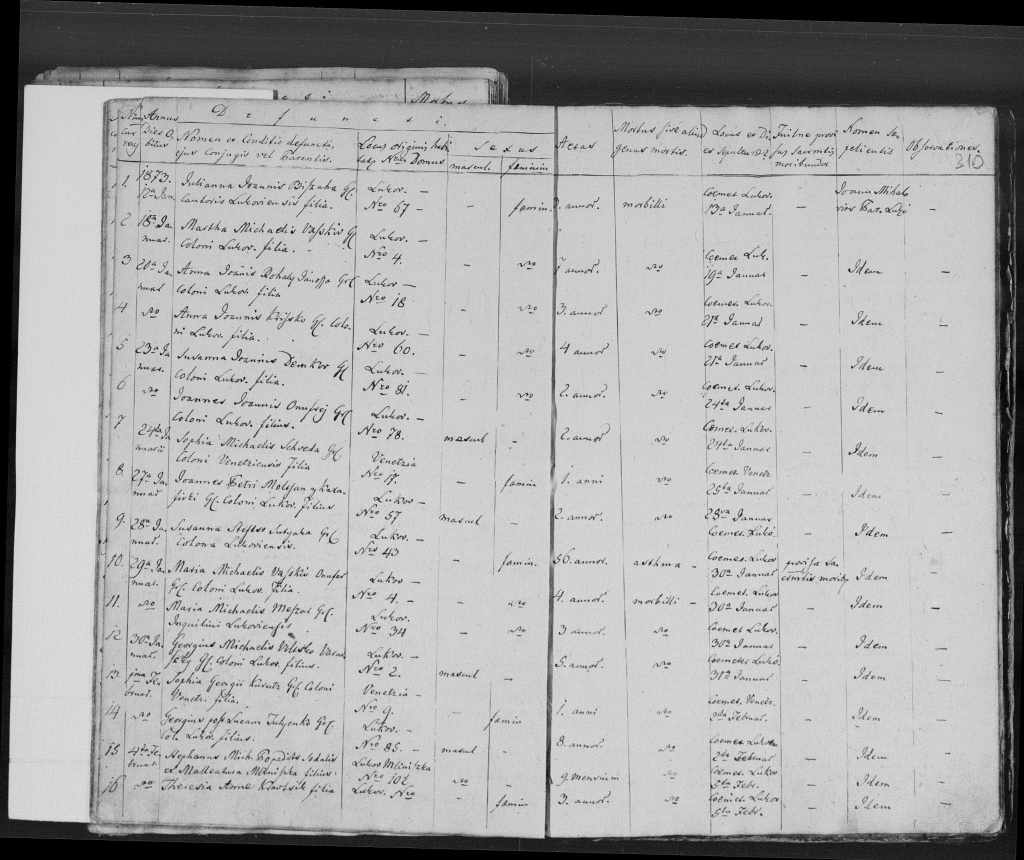

Anna Mikita was born in Lukov-Venecia in 1857 and married Joannes Kuritz in 1878. Joannes was 60 years old at that time, and Anna was his second wife. His first wife, Maria Rohaly, had died of typhus in 1877 along with their 6 year old son, Joannes, in House #12. But wait- there was another young Joannes born in House #12 in 1868 who was now uncounted for… it couldn’t be an error in dates or records because they were meticulously detailed. I had missed the death of the first son, remembering that they simply recycled the names of deceased children according to birth order. I would have to go back to 1868 and pay closer attention to the deaths in the village, the “Morbus sive aliud genus mortis” aka “Illness or Cause of Death.”

“Morbilli.” I thought it meant general death, maybe of an unknown cause, and it killed a lot of children. Between January and March of 1863, 27 children in the village died starting with 2 year old Maria in House # 55 and ending with Susanna, 5 months old, in House #47. A second major wave of “morbilli” hit the village in January 1873 and resulted in the deaths of 37 children. Some quick Google searches later and I had accessed a page of Latin causes of death. Morbilli was measles. In April of that same year, “variola” (smallpox) arrived, killing 4 more children. Adults weren’t spared in 1873- Cholera killed 34 people in Lukov-Venecia between July and September. These weren’t the only deaths that year in the village: diphtheria, thyphus, asthma and colic also took many lives. My ancestors must have been as glad to see the end of 1873 as I was to see the end of 2020. In the midst, I discovered that the first Joannes born to Joannes and Maria Rohaly had died at 6 months old of colic.

I always wondered, long before Covid, what the impact might be if these old church records were used in a public campaign encouraging people to vaccinate their children. Simple posters with photocopies of what it looked like, in factual black and white, when a measles, diphtheria, or pertussis outbreak hit a village in Europe in the 1800s; the physical pain of the disease without relief, the suffering of the children and their families, the devastating grief that would follow the death. Although the potential for childhood death was expected (it took 3 times for my great grandfather’s name of Joannes Kuritz to survive into adulthood), I doubt it was accepted any more than losing a child is today. I wonder what Anna Mikita, Maria Rohaly and Joannes Kurtiz would say if they knew that today we have a simple vaccine for these illnesses that took away their siblings, cousins and children- but that some people refuse to use them. I wonder what the ancestors of anti-vacciners would say, or how they might beg or implore their descendants to rethink their decisions. I think that most of those decisions are made from a place of fear, but I also think there must have been nothing more terrifying for these powerless villagers than the news that measles, smallpox, diphtheria or pertussis were once again spreading through their streets.

The years of research I have done as the self-title “Family Genealogist” have taught me endless life lessons. I have followed my ancestors as they immigrated from modern day Slovakia, Ireland, and Scotland to the Midwest of the United States. Countless men in my family fought in the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, WWI and WWII. My great grandmother traveled from Scotland to Indiana in 1902 with five children under the age of six to meet up with my great grandfather, who had immigrated the year prior to secure work in the coal mines. My paternal grandmother’s letters to her two brothers serving in WWII shed light on a dark and difficult period of history, from polio and quarantine, to food rations, to overwhelming worry and fear. Ultimately, Anna Mikita’s death record was lost during the conversion of church files into the state archives, so her fate remains a search for another day. In the end, I carry these stories with me and when faced with adversity, I often remind myself that if my ancestors could survive life’s challenges, so can I. I cannot understate the amount of pride I have in every one of them, I hope they are proud of me, and I wish to be remembered proudly. There is a tiny blip on a timeline that we get placed on at birth and that timeline continues long after the tiny blip of our death. The goal of humanity, minimally, should be to keep that timeline going with the least amount of pain and suffering as is possible for future timeline riders. We can’t change the past, but if we can make the ride smoother, happier, or less filled with strife for our descendants, isn’t it our obligation to do so?